The long-awaited summer sun finally hit, bringing the classic British humidity that comes when temperatures soar. This heat drives a nationwide urge to dive into cool water, seeking relief in our air-conditioning deprived society.

However, the waters around the UK can still be dangerous, both in terms of temperature and potential hazards. Despite this, wild swimming remains popular and generally safe, though reports of drowning incidents, even among strong swimmers, are on the rise each year.

The media often fails to detail how these tragedies occur, usually attributing them to “difficulties whilst swimming,” “debris,” or “strong currents.” This vague reporting doesn’t sufficiently highlight the actual dangers, leaving people ill-informed.

For example, if someone drowns near a waterfall, it’s often assumed they were just unlucky or poor swimmers. In reality, the powerful “washing machine” effect beneath large waterfalls can drag and hold swimmers under. Understanding these mechanics helps people make safer choices.

Various hidden hazards in bodies of water need better public awareness to prevent avoidable deaths. Rip currents alone kill hundreds annually, yet many don’t know how to escape them.

In this post, I aim to compile the potential dangers in UK waters and beyond. While I’m not a professional, my insights come from personal experience and extensive research on how to stay safe. I highly recommend further reading on safety from the links posted at the end of the post that are from professionals and have further insights.

Cold water shock

Easily one of the most common killers. It can be a scorchingly hot day on the ground, but that lake or river in front of you is still cold enough to send your body into cold water shock. For reference, the most common water temperature for cold water shock is around 10C – 15C but can in instances be even high as 21C-25C. The River Thames on average all year is 12C. At the height of summer it just about makes 18C and on rare occasions peaks at 21C-22C. Similarly sea water around the UK is 8C-10C in the winter and still only 15C-20C in the summer. This should be enough to tell you that cold water shock is a frequent risk.

What happens next after you’ve dived into this deceptively cold water, is that your body goes into a response out of your control. Your blood vessels shrink, your heart works much harder to keep pressure up and your lungs involuntarily make you take a huge 2-3 litre gasp of air in one go, regardless of being underwater or not. When sub-merged, vertigo is also a symptom, making it even harder to know up and down.

So here are the killers –

- A heart attack simply from how hard your heart has to work to keep working in the face of shrinking blood vessels.

- Drowning from the fact that your limbs and muscles are not getting enough blood in them to keep working due to the shrinking of blood vessels.

- Remember that huge involuntary gasp? Well it takes 1.5 litres of sea water to kill you and your lungs just forced you to take at least 2-3 litres of water in from the cold water shock reflex. If the water didn’t manage to go into your lungs and drown you, the sea water in your stomach might! Not to mention after this you continue to hyperventilate so the chances of more water going in is very likely.

What can you do to mitigate this? Well first and foremost, don’t go in or fall in! Fail that, relax and try to regulate your breathing, movements and try to cover your face from inhaling water if hyperventilating. Wearing a lifejacket or buoyancy aid will drastically increase your chances of surviving and being able to regulate yourself. Immersing yourself in for 5 minutes before jumping in can reduce the chances of cold water shock by at least 50%. This is important to remember as cold water shock can also impact those that enter the water intentionally.

The key at the point of immersion and subsequent triggering of cold water shock is to protect your airways and conserve energy. The RNLI’s advice is to stay afloat for 60 to 90 seconds – which is the time cold water shock should start to pass. After this you should be able to regain control of your breathing.

It’s worth highlighting that cold water shock is different from Hypothermia. Hypothermia acts slowly, the key characteristic being that heat is sapped away slowly over time leading to a critical state. Whereas cold water shock is instant and can cause near instant fatality.

Underwater currents

Underwater currents, including rip currents and riptides, are common causes of drowning. Unlike visible dangers, these powerful currents are often hidden beneath calm waters. A seemingly peaceful river can have strong turbulent currents below the surface, and riptides at beaches can be hard to spot from the shore.

Rip currents and riptides pull swimmers out to sea at speeds faster than Olympic swimmers. They occur naturally in surf conditions, helping the ebb and flow of tides and waves. While surfers use rips to reach deeper waters, unsuspecting swimmers can easily panic and exhaust themselves trying to swim straight back to shore, leading to drownings.

Rip currents can also occur in large lakes, river mouths, estuaries, and near man-made structures. Understanding and recognising these hazards is crucial for safety.

As shown in the image, remain calm, tread water, and stay afloat. Use the universal help sign: raise one arm, wave, and call for help. Sometimes, rip currents can loop back to shore. If you’re a strong swimmer and alone, swim horizontally to escape the narrow rip channel, then head back to shore. Never swim against the current, as this will exhaust you.

Swimming between red and yellow flags can help you avoid rips. Choose beaches with lifeguards who can inform you about rips. If there are no lifeguards, check for signs of rips: churning, choppy water, or a break in the surf where water flows back to sea. Watching videos on YouTube about spotting rips can also be helpful. Remember, rips can sometimes be invisible or look like calm water.

Similar to rips are undertows. The most obvious undertow you would have all felt would be the pull of the water right before a wave is about to crash. These one near the shore are ok to deal with as an adult but for small children or weak swimmers a bit further out, it can be potentially dangerous, so one to look out for, as it can make you tumble over repeatedly and hit your head on the sand quite hard.

A similar type of pull occurs near waterfalls. It’s something more to look out for when near large or very high flow waterfalls. The physics are very interesting, regarding critical flow and supercritical flow meeting sub-critical flow. Essentially, at the bottom of any type of waterfall, if the flow reaches a certain level, it creates an effect of re-circulation of the current, basically an underwater whirlpool that sucks in anything near its vicinity. As a swimmer, this would essentially drown you, not to mention the pressure of the waterfall itself being so heavy that even if you could fight the whirlpool current, once you’re underneath, the weight adds to your demise.

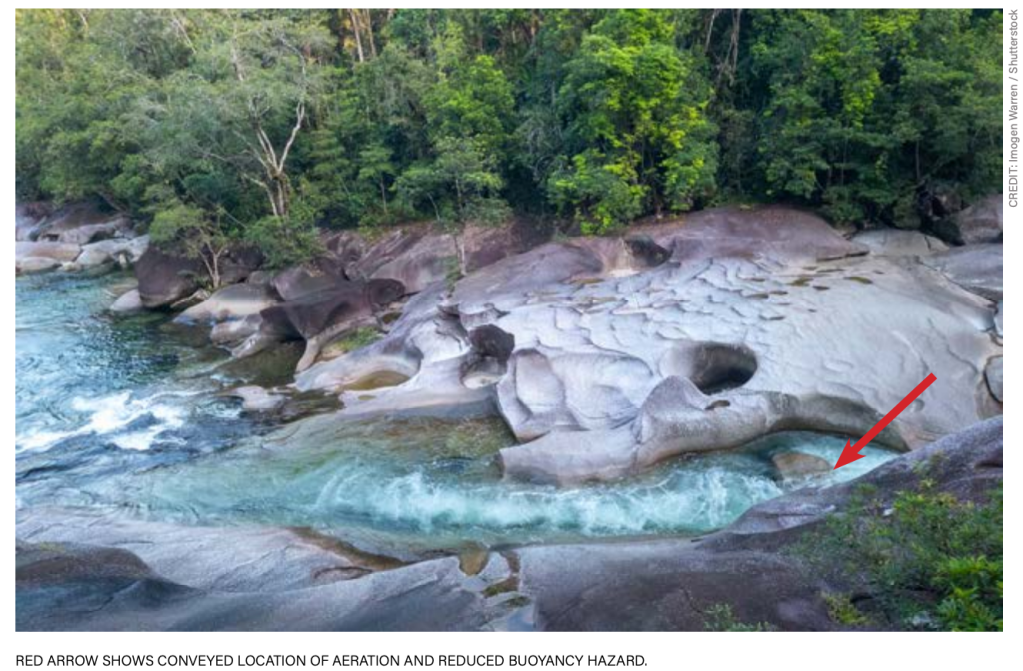

A warning to kayakers/paddle boarders or any other water sports. Something to be very careful of are weirs (low-head dams). Even though they are essentially tiny waterfalls and look harmless, the huge volume of water flowing through can also create this underwater whirlpool effect – trapping your kayak or board in a vicious cycle, this has claimed the lives of many unfortunately. The aeration that occurs around weirs (and waterfalls), which is the formation of air bubbles (white water) also drastically reduces buoyancy, adding to the sinking impact. For this reason, Weirs are notoriously given the nickname “drowning machines”.

Your best chance if ever caught in this type of current near waterfalls or weirs is to get into the outflowing bottom current. Try to relax, swim out to the bottom or side and catch the current at the bottom.

Under Cuts and Underwater Caves

Did you know one of the most dangerous rivers in the world is located right here in the UK? In an unsuspecting peaceful woodland close to the Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire, flows the River Wharfe. Now its a particular section of the River Wharfe called The Strid that is named the most dangerous river in the world. It flows through Strid woods and what makes it a near 100% fatality rate is if you fall in it will instantly suck you into the cave systems underneath the rocks of which there is no escape.

These cave systems exist due to a unique geological formation of rocks that the River Wharfe all of a sudden encounters when going into Strid Woods. As these rock formations are so narrow, for the entirety of the wide River Wharfe to fit through, it has to squeeze in, creating immense pressure. All of this pressure over the eons has caused multiple complex underwater caves to be dug out from underneath the rocks. These are called undercuts and can be full cave systems or partial carvings.

So as in the above picture, where I’m standing is not the real edge of the river. The river is flowing underneath the rockbed I’m standing on. The river for that reason looks deceptively narrow, when in actual fact its flowing side ways and if you were to fall in you would be swept by that sideways currents underneath into the caves. Multiple people have died here from trying to jump over the narrow gap, slipping and falling in. Their bodies can take a month to appear much farther downstream once out of the end of the caves or sometimes are stuck forever.

The dangers of underwater caves and undercuts such as these are obvious once you know about them. Big single boulders and rocks in rivers can also be undercut, either fully through or into a dead end. Both can easily drown you. When an undercut goes right through a rock, it can sometimes be called a Siphon. Watch this incredible footage of someone getting extremely lucky and making it out of the end of one of these Siphons when they accidentally get caught by hitting the rock.

He got extremely lucky that 1. It went all the way through 2. It was wide enough 3. There wasn’t any debris blocking the way or to get caught in. You can see how horrifying it would be and why its so important to be able to recognise these hidden dangers. In the case of Siphons, if you’re in an area with strong currents and white water rapids you may notice a rock with water pounding against it but an area of the rock having clear water instead of aerated white. This is because its going into a Siphon or undercut, be aware!

Remember some undercuts and siphons will just pin you against them or only take you part way through, near impossible to escape.

Debris

In nature, nothing is always clean and neat. Especially after a storm, expect a lot of debris in your potential water spot.

Sometimes debris like a fallen tree or even part of a fallen tree hanging from a bank can cause a type of trapping effect against it. The pressure and weight of the water traps you against it. This is called a Sieve or Strainer.

The best thing to do if you’re caught in one would be to climb on the structure, kick your feet to help you over it. Do not allow yourself to be swept under.

Lack of buoyancy and air bubbles

The crashing of water falling and powerful currents can cause air bubbles and aerate the water. This make the water significantly less dense and so the result is reduced buoyancy. Where you would normally float, in these types of water, you may sink, even when trying to swim. This effect can be very dangerous when combined with all the above, but also when the area is deep. Sometimes there is a “washing machine” effect – illustrated below – that adds to the danger. These are all easily avoidable by not swimming in white water/aerated water unless properly equipped to do so. Sometimes you can see boils coming out of the water, due to the centrifugal movement of the water.

Canyon Magazine states for escape “let yourself sink without resisting the flow and when you come to exit the flow of the washing machine swim hard to exit the flow”. Best to avoid getting in this situation!

Flash floods and water level changes

Do you ever wonder sometimes when you’re hiking along that the ground is just made up of really rounded off pebbles and small rocks? Well this area could be prone to flash floods and you’re actually walking on a dry riverbed! Its not always as obvious and clear as the picture below, but look out for the shape of the pebbles and rocks. See if they look like they’ve been shaped by strong flows of water. Look at your surroundings and take note whether its a flat expanse or resembles anything that has marks of being shaped by flows of water. Most of all, check weather reports, local environmental warning signs and hazards.

Flash floods can be incredibly fast and you can find yourself in an inescapable situation. The best escape really is to make sure to not find yourself in one by being aware of your surroundings, reading up on local warnings and always monitoring weather reports. Fail all of that you’d want to be swimming defensively (protecting head and body) and turning your feet downstream to avoid them being trapped beneath the water. When you spot calm water, you would need to swim across the current, like in a rip, get out and head towards higher ground.

Water level changes are important to consider around popular diving/jumping spots, as they can easily become fatal if levels have dropped or even if currents have moved underwater rocks. Each time you jump, assess the risk and environment. Even if you’ve previously jumped there or seen someone do it.

Final note

Nature is unpredictable, even with all the training and knowledge beforehand, sometimes someone can just get unlucky. However you can mitigate and reduce the risks drastically by being prepared. The best preparation by far is always wearing a lifejacket or buoyancy aid. Buoyancy aids still require you to be able to swim and float to keep your head above the water, but help a lot. They’re smaller and lighter than lifejackets so preferred when doing watersports.

Further reading

https://rnli.org/safety/know-the-risks/rip-currents

http://www.canyonmag.net/technical/safety/hydrology

1 comment